There’s a fight a-brewin’: On September 26th, Emily Wilson’s translation of the ancient Greek epic poem the Iliad was released (published by W.W. Norton), the natural follow-up to her 2018 translation of the Odyssey. That initial project garnered a great deal of attention as being the first published translation of the Odyssey done by a woman—into English. Wilson, for her part, prefers to emphasize her work’s more immediate qualities than her own metahistorical first-ness.

The marketing campaign for Wilson’s Odyssey was very successful, however, due in whatever proportion to usage of the reliable “first woman to ____” narrative, and the book received popular acclaim as well as positive scholarly reviews. To some people, it was their first introduction to the Homeric epic. For others, it was the first time that they really connected to the story, freshly delivered to them in more idiomatically accessible language. In either case, I have anecdotally heard several people say that they first developed a deep personal connection to Homeric poetry and to Odysseus’ story through Wilson’s translation.

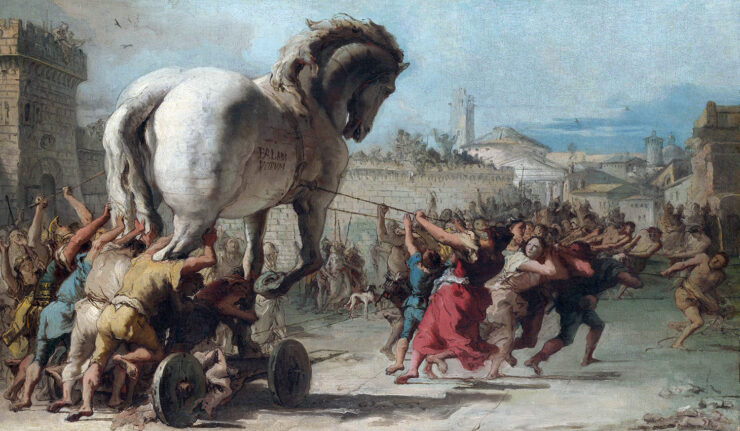

Other people, however, received the first translation of the Odyssey (into English) by a woman with hostility and suspicion. This too is probably ascribable to the emphasis on Wilson’s gender during the translation’s marketing. Why, reactionaries appear to have reasoned, would you put so much emphasis on the “first woman” business unless this new work was a part of some feminist agenda? Why can’t the feminists leave these traditional tales about super men alone? Now once more, with the release of Wilson’s Iliad, the controversy has been revived. At least this time around, the conversation’s nominal centering on the Iliad, the tale of Achilles’ wrath, permits us to make a cute little parallel: both Achilles, the Iliad’s central wrathful hero, and Wilson’s more strident detractors compel us to wonder, “why are you so angry?”

I don’t really wish to litigate here every specific argument that has been raised, or even just the best or worst ones, about what the Homeric epics should really be and how Wilson distorts/misses their essence. But I do wish to reflect on how these arguments play on commonly held notions about the past, for I think they will be pertinent to a fantasy-reading audience.

It is worth mentioning that I will be making some arguments here about what I infer to be broadly held beliefs. Estimating what others believe is at the best of times a tenuous proposition, and I may simply prove to be not a very good barometer. Have I done enough hedging yet? OK, here we go:

There is a lot of fat to cut through in the discourse around Wilson’s work, most of it pertaining to disagreements on translation methodologies. Is it superior to keep the translation as literal as possible, cat for chat, or is there some “spirit” of the original text that it is more important to communicate, one better achieved through the taking of certain liberties? What register of English speech is truest to the style of Homeric Greek? And so on. These are interesting but thorny topics—in whose brambles one can hide an awful lot of ideology.

A couple of weeks before her Iliad’s release, a thread criticizing Wilson’s Odyssey in anticipation of her new work made some waves on Classics Twitter, interrupting everyone’s busy schedule of making niche mythology puns and references—and even broke containment into the broader discourse by dint of being so silly that it unwittingly copied the format of a common meme. (Paging Rebecca Solnit…) One particular claim, though, stood out to me and a number of other rubberneckers: that Wilson’s rendering of the Greek adjective πολύτροπον (polytropon) as “complicated” in the Odyssey’s first line amounts to an “insult” toward Odysseus.

“Tell me about a complicated man.”

(The Odyssey, Book 1, line 1)

It’s a perplexing point, but a telling one, I think, once you untangle its logic. A more primary objection would be that the translation is off, and this objection has also been raised. But Wilson has discussed her methods and reasons for translating just this one specific word this way many, many times. It is metrically felicitous, it employs a similar kind of metaphor to the one at work in the Greek. You will either be persuaded by her explanations or you won’t. But to call the choice an “insult” is a stretch which signals that a larger point is being made—one that’s about values rather than accuracy.

I think it is fair to extrapolate that the real issue here is that “complicated” and many of Wilson’s other choices of diction are not grand enough for certain tastes. Most reactions to Wilson’s style, both the positive and negative accounts, emphasize the accessibility of her language, leading some to titter that the masses can now read the story “without excessive mental interruption.” This is a deeply unworthy criticism that at best confuses verbal floridity for complexity, and at worst snidely hides elitism behind thin intellectualism.

This lack of highfalutin’ talk—though to my ear, it is still plenty falutin’—does not overdetermine for the audience how exalted or virtuous we should think the feats of masculine achievement related in these stories are to the same degree that using language in higher register might have. To some readers, this robs the texts of what (to them) made the poems meaningful. If we are not here to bask in the glory of Achilles and Odysseus and Diomedes and Ajax and their strength and daring, then why did we even show up for the party?

Fortunately, Daniel Walden for The Bulwark has already done an excellent job at cutting through the noise, calling out in his review reactions that confuse “criticism of taste and criticism of merit”:

Wilson has made choices, the same as any other translator has: These choices place emphasis on one thing and not on another. To complain “but there’s more to it than that!” is nearly redundant: of course there is, because we are reading English and not Greek.

Walden does not hesitate either to identify the culprits of that unsophisticated criticism as “culture-war pundits.” The usual suspects, then. But we can say a little more here about what it is that these pundits seem to believe. For whether or not we are politically aligned with the people making these sorts of arguments (whom I infer tend to be more conservative), we might share more ideas about the past with them than we realize, ideas centered around that past’s relative…well, complexity.

That is the supposed distortion taking place at Wilson’s hands, is it not? That she has taken an ancient text about virtue and either injected it with some sort of postmodern moral skepticism, or at least she has introduced it to too wide of an audience who will, by fault of being moderns with modern styles of interpretation, misinterpret it. That is a strange way to talk about art, to insist that it should leave as little room as possible for people to misunderstand, i.e., have a different perspective from yours.

It is, however, a legibly less strange way to talk about an artifact. Unlike art, where we might be more forgiving of differences in perspective borne out by critical engagement, we expect artifacts to represent a particular moment in time. The artifact tends to get held out as a more purely educational object, and as such it ought to impart clear, standard information. This will be on the test. Thus, our understanding of the artifact needs to be relatively simple. If it is very old, we might even be given to think that the culture the artifact represents really was relatively simple, in the senses of being less large, less diverse, and perhaps less self-reflective.

So here’s the crux: I suspect that we are collectively inclined to treat the Homeric epics as artifacts. They are supposed to represent an idea of ancient Greece to us, and arch narratives of historical progress prime us to accept that past societies were scientifically, politically, and ethically less complicated. Thus, we as readers may expect the Homeric epics to reflect a relatively simplistic worldview, one that is, say, uncritical of patriarchal hegemony—and we can believe that without, as some people do, trying to use it as an argument in favor of patriarchal values.

It is worth pointing out, then, that the Homeric epics invite a lot of ambivalence about the heroic world they portray.

The closest they ever come to a tidy moral lesson that I can think of is Menelaus’ statement on ideal hospitality in Odyssey book 15, imparted upon hearing that Telemachus would like to go home now, please:

I disapprove of too much friendliness

And of too much standoffishness. A balance

Is best. To force a visitor to stay

Is just as bad as pushing him to go.

Be kind to guests when they are visiting,

Then help them on their way. […](Trans. Emily Wilson)

And this is a rare universal truth, Homer. Well done. Anyone who has ever desperately tried to excuse themself from an interminable party will understand.

But neat universal truths delivered didactically are few and far between here, even more so in the Iliad than the Odyssey. Some may try to describe the former, the tale of Achilles, as one about the importance of glory over even life itself, a study in macho-ness—delivered direct from the time when men were men! I won’t outright say that this reading is wrong. It is certainly not completely out of touch with the text, which is indeed deeply concerned with honor, both that which must be paid to the gods and goddesses (Hera and Athena’s sense of slighted honor is deliciously palpable whenever they appear) and that which mortals can scrape together for themselves while they live.

But I think it is more correct to say that the poem is depicting the difficulty, nigh impossibility even, for mortals of weighing those two goods against each other, life versus glory, happiness versus honor. What is impressive about Achilles is that he bothers to stop and really try to hash out the answer. What is tragic about him is that in his selfish deliberation, he loses more than he bargained on—the life of his dearest friend. Now Achilles’ chance for a long life is gone, and the glory he purchased with it is not as sweet as he hoped. There is emotional catharsis, but no clean resolution to take home like a trophy once the dust has settled, and we and Achilles are left to make peace with that.

There is, of course, “more to it than that.” Different Greek heroes strut their hour upon the stage in Achilles’ absence (Diomedes clocks in a few more hours than others), Trojan champion Hector—contrary to the sweet, Eric Bana-fied version of him that occupies the popular consciousness—sinks slowly deeper into his own war-madness the longer he fights, and human and Olympian politics play out to alternatingly dramatic and comedic effect. There are a hundred little moments of big emotion.

The venerable Ursula K. Le Guin wrote about Homer on her blog (she had a blog!) back in 2011:

People keep going to him and discovering new things, or old things, or things for the first time, or things all over again, and saying them. This has been going on for two or three millennia. That is an amazingly long time for anything to mean anything to anybody.

Le Guin understands the magic. It’s in how these stories, with their many sparkling facets, make you think and feel, not in what they instruct you to believe.

This is also where the fantasy genre comes into our discussion, for Le Guin’s new-old observation this time is that the Iliad and the Odyssey serve as ur examples of the two basic types of fantasy, the War and the Journey. (“I’m sure,” she notes, “this has occurred to others.”) But the big sticking point, what impresses Le Guin about Homer, is that he does not do the War like the many fantasies that followed in his wake. He does it better.

Le Guin takes issue with how most contemporary fantasy wars reduce the conflict to Good vs. Evil (the BBGE, she dubs it: Battle Between Good and Evil). Homer’s war, by contrast, is only people vs. people, and in those non-absolute terms it makes space for human tragedy in a way that the other kind of story can’t contain:

In the War of Good vs. Evil there can be divine or supernal justice but not human tragedy. It is by definition, technically, comic (as in The Divine Comedy): the good guys win. It has a happy ending. If the bad guys beat the good guys, unhappy ending, that’s mere reversal, flip side of the same coin. The author is not impartial. Dystopia is not tragedy.

There’s a not-so-subtle genre rebuke here over how fantasy tropes of Good battling Evil elide complexity in order to make a power fantasy. That point is itself a bit reductive, we might object, in the way that all generalizations are. We could communally probably produce a whole catalog of examples of tortured heroes (and villains) whose psychological woes keep readers from thinking that the life of a sword-swinging champion is too much fun.

Frodo Baggins immediately jumps to mind, who is not even a mighty warrior but only a humble hobbit carrying the One Ring, the essence of Evil, to where it can be destroyed. No one envies Frodo’s lot. It breaks him in ways that will never fully mend. Rand al’Thor from The Wheel of Time series, which often feels like The Lord of the Rings in photo negative, wields a tainted magic that will someday snuff out his sanity and cause him to turn on his loved ones (Greek myth scholars call that one “the Herakles.” For the inverse of this dynamic see “the Ajax”). In creating Elric of Melniboné’s vampiric runesword, Stormbringer, one gets the sense that Michael Moorcock is suggesting that all swords are really vampires that seduce and corrupt their otherwise virtuous wielders—or even if he didn’t intend it, we can still think that.

Even Le Guin herself goes in for this sort of heroic struggle in her Earthsea series. In the fourth and fifth books, the wizard Ged makes a great personal sacrifice to right the natural order of the world and subsequently must muddle his way through a kind of metaphysical bereavement.

But there is a difference between a hero who suffers in the name of his quest, which audiences are given to find ennobling and worthy in its own way, and protagonists who act in an indifferent moral landscape where the goalposts for “right” and “wrong” are not clearly established. The former are usually making a sacrifice, which is a hard decision, but one made with a certain idea of what they or the community are getting in return. The latter can experience loss without any framework to make it meaningful. That’s what Le Guin means when she talks about the “tragic,” I think. Loss existing without the comfort of some crude utilitarian gain.

The former sort of story isn’t wrong to tell or to enjoy, obviously, and it is even a useful tool for us to theorize about the nature of capital-E Evil (or conversely of Good). But the division of Good and Evil into clear, opposing camps will tend to simplify the moral calculus. Who is doing the Bad Thing? Just those guys over there. That’s part of the appeal of a solid Good vs. Evil story. They offer the comforting certainty of simplicity. Their heroes may sometimes be at a loss for what to do in the moment, but they are sure of their quest, their larger goal. We might sometimes call that “escapism”—which is yet another idea Le Guin wrote about on her blog. She’s pro-escapism, as she is pro-Homer, for its imaginative potential to confound simple, orthodox ways of thinking. But when it comes to the fantasy war, the BBGE, we probably ought to consider whether what we are escaping toward is a scenario where violence is inevitable and justified, which does not sound like much of an escape from our reality at all. Well, at least in fantasy, then it’s time to break out those super cool magical swords, baby! They all have names; I named mine Jessica.

Now, fictional violence is fun and kinetic and tense, all great things for fiction to be. I couldn’t get rid of it if I wanted to, and I don’t want to. It’s harder to make a narrative of normalizing diplomatic relations as exciting. We are just acknowledging here that the war of Good vs Evil, the setting for uncomplicated, fun violence, finds itself a ready home in the fantasy genre, which mostly consists of pseudo-historical settings, medievalesque societies and even more distant pasts in the case of sword-and-sandal stories. These fictional approximations of the past are presented as less complicated times. And if they didn’t exist, I would have nowhere to take Jessica.

Buy the Book

The Iliad: Translated by Emily Wilson

What is interesting about the Iliad—and what reactions to Wilson’s translation, along with Le Guin’s old blog post, have got me thinking about—is how it gives the lie to this notion that the ancient past—or at least its art—was restricted to the fabular and allegorical, morally prescriptive and didactic. That’s the way that I used to approach Greek myth, anyway. It’s not a reading framework I find that the Iliad or the Odyssey naturally fit into, which ought to be part of their appeal. I worry a little that the reviews which paint them in some totalizing manner (generally in an effort to get a dig at Wilson for missing the “one thing” about them) will turn off potential readers by making them seem more banal than they are.

I do want to tread a delicate line here and not imply that the epics were, in total contradiction of reactionary appropriations of them, secretly progressive all along. They’re not.

The Odyssey is a deeply misogynist story, not just incidentally, through matter-of-fact descriptions of the patriarchal culture in which it is set, but concertedly and thematically. The figures of Helen and Clytemnestra loom large in the text as paradigmatic “bad wives,” unfaithful and homicidal, in whose footsteps Odysseus must ensure his own wife, Penelope, has not followed. Agamemnon’s ghost stresses this to Odysseus, and that point, more than the not-so-helpful prophecy of Tiresias, feels like the true important lesson of his visit to the underworld.

And the Iliad is a story impressed by the heroic capacity to commit incredible violence. It is important and impressive that Achilles is the best at violence and has got the biggest spear. That’s not me making a funny, by the way. That’s a fact emphasized in the narrative. Book Sixteen, line 140, get a copy and see for yourself! Oh, Achilles, how will your boyfriend manage your big, enormous spear? He can’t. Patroclus has to leave it behind when he borrows the rest of Achilles’ gear. It’s just too big for him. It is an unsubtle signifier, but—look, subtlety and nuance are different things.

But these aspects of the epics are not created, as they may be in the hands of a lesser storyteller, through incurious and uncritical depictions of either women’s motivations or men’s pride. Homeric women have as much emotional and intellectual depth as the men—I’ll even disagree with Le Guin around this particular point; I think she reads Homer’s Helen as more shallow than the poet portrays her as—and Achilles’ and Odysseus’ unbending need to be lavishly credited for their greatness is a constant and unambiguous source of their folly. Is there a word for that idea? A Greek word, perhaps? I’m not sure; I’ve never heard of one…

There is a lot more we could say about the Iliad and the Odyssey here—and have said, and will say—because there’s no one thing to say about them that feels sufficient. Thus, coming to any conclusion on the subject always also feels a bit artificial, and the only one I can deliver here that feels honest, complete, and adequate is to say that I really love these poems. Considering the misogyny—this is not an imaginary past to which I yearn to return—maybe sometimes my love is as Mr. Darcy loves Elizabeth, “against my better judgement.” But my feelings will not be repressed.

I love the heroes’ big man emotions, the manipulative goddesses, the whole forest of metaphors about falling trees, and—one of my all-time favorite fantasy motifs—adoring descriptions of Really Cool Stuff. I also love their sometimes surprising and never mawkish depictions of tenderness between people, even people who are deeply out of harmony with one another, as Hector is with Andromache, or Achilles with Patroclus. I guess what I’m trying to say is, marry me, Homer. I have 10,000 a year. Your weirdo family doesn’t have to be in the picture.

I don’t think the epics are stories that will liberate me, teach me virtue, or even necessarily exalt my soul. For reasons of the dilated nature of their composition, they may not be the best document for learning about any one period in Greek history, either. But at least I love them for what they really are.

Ursula K. Le Guin and Emily Wilson seem to feel the same. Indeed, this, Wilson has repeatedly testified, is the true premise of her translation project: to render the poems in an as unmediated a way as a translator feasibly can, so that even more people can love them just as they are.

Kristen holds a master’s degree in Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies, but she also holds strong opinions on subjects in which she is not formally accredited. She reads. She is always trying to read more, MORE!